| ISSUE BRIEF | ||||||||

|

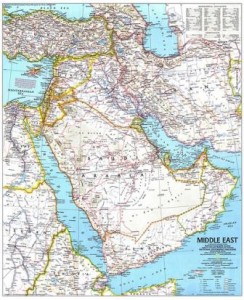

Between Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, they have massive financial resources at their disposal for investment abroad and backing their policies both domestically and abroad. Both Iran and Iraq are potentially exceedingly rich though they are in difficult circumstances currently.

These countries also constitute the physical and theological heartland of Islam for both the major sects – Shia and Sunni. The location of this sub region of West Asia has enormous strategic significance. For all these important reasons all major countries of the world have a great interest in the stability and security of the Persian Gulf region.

I

The Persian Gulf : Changing Scenario

Consequent on the absolutely unprecedented winds of change blowing through the Arab world for the past two years, in outcomes which no one had predicted or could have even imagined, dictators exercising absolute power for decades were overthrown in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen. A destructive civil war is raging in Syria with the overthrow of yet another authoritarian ruler the most likely outcome. In other Arab countries, particularly in the monarchical states, regime preservation and security has become the preeminent priority of the rulers, whatever the costs incurred in the process.

Islamist parties have been elected and formed governments in Egypt and Tunisia but both countries continue to be wracked by very considerable political instability; the situation is far worse and quite unstable in Libya and Yemen.

Since Syria is an overwhelmingly Sunni majority country, in the backdrop of the increasing sectarian divide in West Asia, any new governmental set up in Syria will inevitably have a distinctly Sunni Islamist hue. Both moderate and extremist Islamist groupings are very active in all these five countries as well as in Iraq. The rise of political Islam and the resurgence of radical Islam are potent new phenomena which will have security consequences and also have a transforming impact on the external relations of these Arab countries with the outside world.

The estimated Shiite population percentages of GCC countries are: Bahrain around 70 %; Kuwait about 30 %; Saudi Arabia about 18%; Qatar and UAE about 10 %; and, Oman about 8 %. About 65 % of Iraqis are Shia. Including Iran – which is 90% Shia, more than 60 % of the combined populations of the 8 countries of the Gulf region are Shia. Yemen has a 35-40% Shia population.

More than 50 % of the Arab Gulf region’s oil reserves are located in the Shiite populated parts of the region. Following the US engineered downfall of the Sunni regime in Iraq, Shia political forces emerged as the predominant component of the country’s ruling dispensation for the first time in modern history. Iran now has much more influence in Iraq than fellow Arab countries. The Shias of Iraq and the GCC countries have been consistently treated as second class citizens. Shias see Iran as an inspiration. There is a huge and unbridgeable asymmetry between the GCC countries’ national power and that of Iran in terms of demography, institutional capacity, military manpower strength and indigenous capability. All these features provide Iran enormous potential leverage in exploiting Shiite identity to disturb, even reshape, the balance of power in the Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Gulf region. Saudi Arabia has become increasing more acutely aware and traumatically afraid of these realities.

The Arab Spring fever spread to Bahrain from North Africa very quickly and Saudi Arabia immediately accused Iran of instigating the huge daily protests and demonstrations and soon thereafter dispatched troops to Bahrain making it abundantly clear that the regime there will not be allowed to fall or indeed in any GCC state. Adopting the principle that offence is the best form of defence, Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries, launched a high profile campaign against Iran. Syria has been Iran’s staunchest ally in the Arab world and the main conduit of its influence in the Levant. If Assad’s regime were to fall, Iran would find it virtually impossible to continue supporting Hezbollah and Iranian influence in the sensitive Levantine region would be dealt a virtual death blow. Iran’s ability to play a role in Arab politics would be severely curtailed.

What had begun as domestic protests against President Bashar Al Assad’s regime has quickly transformed into a virtual civil war partly because of Assad’s misplaced and arrogant self confidence that he could crush the ‘rebels’. And also partly due to Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey funding and arming the dissidents and making Assad’s removal a publicly announced objective, an objective fully shared by US and Western countries. Thus, Syria has become the big prize in the Saudi-Iranian confrontation. GCC-Iran relations have deteriorated sharply, further exacerbating the edgy salience of Iran’s internationally worrisome nuclear programme.

II

Existing Security Architecture in the Persian Gulf

The existing security architecture was created by the US which essentially offered to safeguard the security and control of the ruling dispensations over their domains and populations and in return the latter ensured that US interests in the region would be looked after. This, over time, has entailed a growing US presence on the ground in the Persian Gulf region to meet changing security exigencies.

The Carter Doctrine has defined US approach to the region since the 1980s; it found expression in the “dual containment” policies against Iraq and Iran in the 1990s and provided the fundamental rationale for military operations in and around the Persian Gulf region starting with the first Persian Gulf War in 1990-91, the war in Afghanistan since 2001 and the second Persian Gulf War in 2003.

All this has resulted in a permanent and growing US military presence in the region through the 1990s to the present. All US troops, which had reached a high of over 500000 in 1991, were pulled out of Saudi Arabia by the summer of 2003 and bases closed. However, recently it has come to light that US has been operating drones against Yemen from a secret base in Saudi Arabia. US troops were finally withdrawn from Iraq in late 2011 and early 2012 and are slated to be withdrawn from Afghanistan by 2014. However, bases with varying numbers of troops exist in the other five GCC countries with Bahrain hosting the Fifth Fleet since 1995 and Qatar the Central Command since 2002.

Though hardly mentioned in academic discourse on the subject, Pakistan has had a traditionally strong role and involvement in regime security in the GCC countries and it may come into play if there is large scale internal unrest in GCC countries, as has been witnessed in Bahrain. In other new developments, Turkey has emerged as a player of rising importance and Egypt is a putative player of great significance.

China and Russia have provided Iran with diplomatic protection from being completely crippled as a consequence of American policy and their roles are a part of the regional security scenario. China has had a major arms supply relationship with Iran and has been involved significantly in the nuclear field too as has Russia. China and Russia are providing Iran’s closest ally, Syria very significant diplomatic support by preventing any UN approved punitive measures against it. These relationships have obstructed the furtherance of the US brokered attempt to cripple Iran strategically.

One significant new feature has emerged, and that is to be welcomed, since regional countries should have the primary responsibility for the security of the region. The GCC countries had been passive spectators of security threatening developments in the region in the past but have become proactive participants in shaping outcomes in Libya, Syria and Yemen in the past two years. Overcoming the inertia of the past, GCC countries, individually and collectively, have been playing uncharacteristically proactive and substantive roles in supporting and helping each other and taking adversaries head-on. Both Qatar and Saudi Arabia have provided huge packages of financial aid to poorer brother monarchical states and to the newly emerged regimes.

Regimes in the GCC countries will increasingly band together to ensure that monarchical regimes will not be allowed to be overthrown in any GCC country and their policies in Bahrain represented consciously thought out signals to the world and even to their own people. If any monarchical regime falls, it will be far more due to internal politics within royal families in connection with issues associated with succession to rather than brought about by public demonstrations. A considerably expanded role for them in the region’s security dynamics can be foreseen.

III

The Future of Persian Gulf Security

There is reason to believe that understandings are possible on the nuclear issue but it is ultimately the overarching contradictory political aims and objectives of the different players that stand in the way. Even though relations between GCC countries with Iran have been mostly marked by periods of intense tension, considerable empirical evidence of high level interaction on a continuing basis is readily available in the public domain that suggests that possibilities of non confrontational co-existence should not be dismissed. The challenge is to convert these possibilities into probabilities.

Iran is the pivotal country in the region’s security calculus. Sanctions have been a major feature of the American policy towards Iran since the 1979 Islamic revolution. These were supplemented by sanctions imposed under the authority of the UN since 2006 in the context of Iran’s nuclear programme and later by other entities such as the EU and bilaterally by some countries.

In addition, there are unilateral US sanctions which prevent business entities in third countries having economic and energy relationships with Iran since they would risk their business and economic links with the United States by doing so. This has, inter alia, effectively resulted in Iran’s oil exports plummeting by almost 50% in the past year. All this is designed to cripple Iran economically to pressurize it to change its strategic policies but the unarticulated sub text is regime change. All this is hurting Iran greatly but so far Iran has not caved in. As pressures are relentlessly ratcheted up against Iran the prospects of a military confrontation have been increasing although a full scale conflict is unlikely. Brinksmanship continues by all sides but this is counterproductive and serves nobody’s interests.

What had been considered so far as the main foundation of regional security is ironically viewed as a growing source of insecurity by an increasing number of people in the region. US presence has been the dominant and strongly entrenched feature of the region’s security arrangements. However, this has been creating growing popular resentment against the US and regimes dependent upon the US security umbrella and is providing fuel for the rise of status quo threatening Islamist forces. These tendencies will only gather more momentum in the aftermath of the ongoing changes in the Arab world. The US led sanctions oriented approach to meet presumed security threats from Iran adds to security volatility. After its virtual failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, despite huge costs in blood and treasure, and consequent serious economic pressures upon it, the US appears to be a much-diminished power in the region. The past two years have seen Obama clearly signal that he will be focusing on internal regeneration; he has decisively broken with the aggressive, unilateralist and militaristic approaches of the Bush Administration.

Existing security arrangements may not be adequate or suitable to address the challenges of the future. The insertion of new elements is necessary. The current militaristic and military alliance dominated, zero sum outcomes oriented, exclusivist approaches need to be supplemented by dialogue based, compromise oriented inclusive approaches. A winner take all and loser lose all approach will not work; compromises will have to be made by all players, regional and non-regional; frankly, it is doubtful whether existing partnerships and alliances will be able to navigate through the increasingly complex problems which clearly loom ever larger on the horizon. Out of the box thinking is needed to carve out new arrangements to supplement the existing arrangements. The phrase “supplement” rather than replace, has been deliberately used because the reality is that US presence and role in the region is not about to change any time soon.

IV

A Potential Role for Asia

The Persian Gulf region has become particularly important for other Asian countries and indeed will become even more so in the years to come given the increasing symbiotic connections between the two sides.

The following facts substantiate this assertion:

Asia is in the process of displacing the West as the fulcrum of the global economy and China and India are the leading locomotives. The top four countries in PPP terms in the world are the US, China, India and Japan. Last month China displaced the US as the world’s top trading nation and is forecast to overtake United States as the world’s leading economy by 2016.

The major Asian economies, both developed and still developing, have collectively become the largest buyer of hydrocarbons from the Persian Gulf region. Their demands are projected to keep increasing and substantially. The Persian Gulf region’s role as an energy supplier for Asia will continue to enlarge incrementally for the foreseeable future, even as America’s requirements of oil and gas from the Persian Gulf region are projected to diminish dramatically.

Beyond the hydrocarbons factor, other economic links – trade and investment – between the Persian Gulf region and the rest of Asia are growing very rapidly and indeed are also poised to overtake the economic relationship between the Persian Gulf region and the Western world within this decade.

More than 15 million nationals of Asian countries, mainly from South Asia and the Philippines, live and work in the Persian Gulf countries. There is a tendency to take this for granted but this factor alone and by itself underlines the immense importance of security and stability in the Persian Gulf for Asian countries. Remittances sent home by them are extremely important socio economic factors in the countries of origin of these people.

The other side of the coin is that the huge presence of expatriates has a potentially adverse cultural impact on the local populations of the Persian Gulf region and even potential security implications. This is another reason for Asian involvement in regional security dialogues.

Growing strategic synergies in the energy, economic and diaspora related domains between countries of the Persian Gulf region and of other parts of Asia have become a strategic factor of growing importance for the Persian Gulf region. Besides, peace and stability in the Persian Gulf region have become factors of increasing strategic and even existential significance for the major Asian countries. Another plus is that, barring Pakistan, none of the Asian countries that have an increasing economic relationship with countries of the region have any selfish political agenda of their own in this region.

Over the past few years leaders of GCC countries have been suggesting that the time may have come for Asia to be involved in the Persian Gulf region. Prince Saud Al-Faisal, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Saudi Arabia, gave a wide-ranging and particularly thought provoking speech in Manama, Bahrain, on December 5, 2004. The subject was ‘Towards a New Framework for Regional Security’. He was appointed Foreign Minister in 1975 and is currently the world’s longest-serving incumbent foreign minister. He has seen it all. Therefore, his speech deserves very close attention; in fact, even more so today than when it was delivered 8 years ago. One of several significant sentences from that speech deserves to be highlighted: “……the international component of the suggested Persian Gulf security framework should engage positively the emerging Asian powers as well, especially China and India.” The Manama Dialogue 2006 outcome paper said that “Asia states have ever deeper economic and political links in the Persian Gulf and are likely to find that they will struggle to avoid involvement in the area’s delicate politics if they are to advance their commercial aims.”

The Emir of Qatar speaking at the UN General Assembly, even as far back as 2007, had said: “the major conflicts in the world had become too big for one single power to handle them on its own”.

King Abdullah showed the way dramatically. Given the past unusually strong special relationship between the Saudi Royal family and the US, King Abdullah’s choice of China and India as the first two destinations to pay State Visits to after ascending the throne was a deliberate, path breaking development.

Such tendencies are acquiring rapidly increasing salience and are also manifested in increasing bilateral anti-terrorism, defence and security cooperation between individual Asian and GCC countries as well as in the growing density of exchange of visits of leaders and other high level dignitaries between China, India, Japan and Korea and the Persian Gulf States during the past decade. All this is a very clear indication of new foreign relations related thinking in the GCC countries.

The key lies in finding interlocutors who have credibility and good relations with the GCC countries and Iran on the one hand and the US and Israel on the other. Asia provides these interlocutors – China, and India and Japan; all three are major global powers with rising stature.

Therefore, Asian involvement in the security dynamics of the region is likely to be a win-win situation for all parties, regional and non regional.

The Way Forward: Towards a New Security Architecture in the Persian Gulf

Though each region has its own specificities, the security related dialogue architecture created by Asean through its Dialogue Partners’ network, the ARF, mechanisms such as Asean + 1, Asean + 3, the East Asian Summit, etc., involving all players who have interests in the region, could be templates worth examining. Hardly anybody would contest that these arrangements have helped in keeping the Asia Pacific region peaceful despite the existence of a large number of serious disputes.

Any new architecture that is created should be done at the initiative of regional countries; GCC countries should take the initiative to do this. Iran and Iraq would almost certainly welcome Asian involvement. Any such architecture would ultimately need to include the P-5 and EU; India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia and Pakistan; Egypt, Israel, Turkey and Yemen apart from Iran and Iraq. This will inevitably be a slow, gradual and incremental process but a beginning should be made now.

It is proposed to have closed door Workshops with open ended time schedules be convened under the auspices of institutions like the Gulf Research Centre, the Qatar Foundation, the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, or any other institution considered appropriate and charged with (a) reviewing the literature relating to the subject including compiling a comprehensive list of previous proposals and culling elements relevant to contemporary conditions; (b) creating a detailed data base of the linkages between the region and relevant Asian countries; and, (c) engaging intensively to create potentially workable supplementary security frameworks for the Persian Gulf region.

The Workshops would initially bring together small teams from Saudi Arabia, Qatar and UAE on the one hand and China, India, Japan and Pakistan on the other as well as Iran; the members ideally should be retired diplomats, retired armed forces officers and academics specialising in regional security issues to be appointed in consultation with the concerned governments so that the exercise has credibility.

آخرین دیدگاهها